02/06/2023

There are many explanations concerning what makes a text a ‘classic’. According to the author, a classic text may be defined as one which stands the test of time due to its ability to connect with and convey a popular or shared human experience, as culturally framed by the zeitgeist – or spirit of the times – of which it is created within. In this way, a classic text represents themes and conveys messages which speak to the human spirit of the populace. A culture remembers and cherishes these texts above others because of its sophisticated embodiment of a significant human experience. Calvino (1986) theorises classic texts to ‘camouflage themselves as the collective or individual unconscious’ where meanings are treasured (p. 2). This supports my definition of a ‘classic text’, where a significant amount of the populace greatly connects to the narrative.

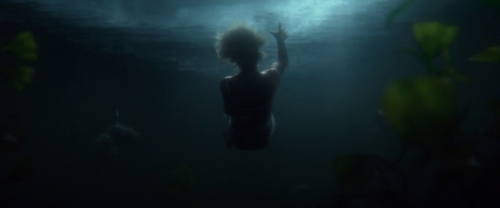

Gone Girl (2014) is a highly popular crime-thriller film even today, nine years after its release, as it continues to garner attention online, sparking dialogue about its representations and meanings. As a film adaptation of the 2012 crime-thriller novel by Gillian Flynn, Gone Girl is an example of how giving a story a platform can allow it to effectively reach and influence the masses. The film is praised critically and commercially, being Fincher’s highest-grossing film thus far. Audiences are drawn to the film due to its highly engaging narrative, where Nick Dunne navigates the sudden disappearance of his wife, Amy, under the media spotlight – as Amy leaves behind a string of clues. It critically embodies the human experience of female rage. Accordingly, Gone Girl should be identified as a ‘contemporary classic text’ because of the sophisticated way that it represents marriage, gender dynamics and feminist characterisation as a hybrid-genre thriller, of which the modern cultural landscape continues to relish.

Gone Girl, in essence, is a sinister depiction of a broken marriage. The brutal and seductive Amy meets the unreliable and arrogant Nick Dunne – a couple of whom provides social commentary on the politics of marriage, especially during a time when marriages are becoming increasingly difficult to sustain. Audiences infer that marriage is a concept which benefits men more than women, of whom must carry the domestic burdens of a home while simultaneously maintain a career, as Amy demonstrates in the film’s montages. In the context of the 2008 economic downfall, Gone Girl provides commentary on western consumer capitalist culture which impedes on marriage. Osborne (2017) describes Gone Girl as an ‘outlet for female rage’ as a response to such a culture which ‘impedes female happiness through inequality in marriage’ (p. 1). With high divorce rates, marriage becomes increasingly demanding and an idol of worship in such a ‘utopic’ America, and an ‘arena in which those involved strive to maintain power’ (Osborne 2017, p. 3, 4). This competitiveness is present in the film as Amy remains the breadwinner of the couple, even financing Nick’s business, which hinders his masculinity. His discovered infidelity towards Amy also speaks to female audiences, forming an emotional anchor in Amy’s decision to disappear. This can be observed as his attempt at ‘reclaiming his masculinity’ after the anxiety of losing his previous work due to the recession (Osborne 2017, p. 6).

The socio-cultural significance of these concepts is that the populace is beginning to question the sanctity of marriage in a society which increasingly moves towards economic and political turmoil. This includes less Western religious affiliation, somewhat-increasing social gender equality and American political betrayal of the lives of women and children – with anti-abortion laws and silence on gun control as some examples. Female audiences particularly feel seen by the portrayal of the theme of marriage in Gone Girl, voicing their concerns with extremity. This cultural fear about marriage resonates with horror theory – of which the thriller may be seen as a subgenre of – as an illustrator of ‘phobias of the new world’ (Wells 2000, as cited in Lee 2023, 25:11). As a crime-thriller, the horrors in Gone Girl, including the depictions of violence, murder and betrayal, reflects ‘an anxiety around change and the unknown’ regarding the sanctity of marriage (Lee 2023, 23:25). The ambiguous future of the validity of marriage in an increasingly polarised socio-political world is thus key to the positive reception of Gone Girl – and essential as to why the film should be considered a ‘contemporary classic’.

The gender power dynamics in the film’s narrative also have a significant effect on audiences. In Gone Girl, the wife is smarter and more successful than the husband, which has thoughtful implications on their gender dynamics. Nick asserts his dominance in the relationship despite his shortcomings, while Amy struggles to be level with Nick through verbal challenge – but the society and home she belongs to works against this struggle, where she will always remain inferior. This dynamic speaks to women who experience similar concepts in their own personal and professional lives under the patriarchy. Stratton (2020) addresses female masculinity in Gone Girl, where exaggerated gender roles are imposed on both Nick and Amy during the media frenzy after Amy’s disappearance. Nick must ‘enact and perform femininity that reads as innocent’ for the news coverage (Stratton 2020, p. 21). Audiences thus perceive the enactment of femininity as a facilitator of power, which has severe implications on the value of the female experience. Audiences learn that Amy sought revenge because Nick ‘epitomised masculinity’ in their marriage, including having a lack of attention to detail to her feelings (Stratton 2020, p. 22). These narrative elements portray a woman who struggles against a gender binary of which benefits men in any circumstance, even when they enact femininity themselves – something that resonates with female audiences under the patriarchy.

‘Amy is a hyperbolised idea of society’s high expectations for women’, where she gradually descends to revenge when she is otherwise expected to suppress her rage (The Take 2020, 4:08). Through her disappearance, which initially frames Nick as the culprit, Amy attempts to ‘turn these gender roles against him’ where the audience doesn’t believe his innocence due to his ‘off-putting’ disingenuity (8:20, 10:50). Combined with Amy’s cunning ability to control her emotions, these elements represent a ‘revenge fantasy against entitled men’ of which highly appeals to the female audience (13:50). The complex representations of gendered power dynamics in Gone Girl’s thriller narrative are thus highly effective in establishing the film as a ‘classic’. Nick and Amy’s thoughts and actions are familiar yet exaggerated tropes which reflect collective cultural anxieties about gender and power, making the film a voice for these concerns. The implications of Nick and Amy’s dynamic is crucial to the success of Gone Girl, a film which connects to the populace by illuminating the multiplicity of the gendered experience, and thus should be considered a ‘classic’.

The characterisation of Amy is another crucial factor in Gone Girl’s premise in being a ‘classic text’. Audiences are remembering Amy as a ‘feminist icon’, rather than simply a sociopathic killer, which implies critical engagement of audiences with the film’s meanings, signalling its ability to portray feminist concerns. As she embodies the female experience, Amy’s character allows the viewer to feel perceived and understood in a complex way that is not conveyed in mainstream media, making Gone Girl shine above ‘the rest’. Martins (2017) identifies Amy as a ‘modern femme fatale’ in the film’s noir tropes – a genre of which Fincher specialises in (p. 101). Amy is a ‘seductive, deadly woman’ who does not ‘pay for her madness’ through death as in traditional film noir, but instead holds her husband accountable for his actions (Martins 2017, p. 102, 106). As audiences infer these meanings through this exaggerated depiction of the everyday female struggle, they celebrate along with Amy her triumph in the domestic and social battle of the sexes. It is important for such portrayals to exist in media, ones where women are ‘just as evil as men are allowed to be’, because it deconstructs the contemporary cultural expectations of women to be perfect (Burkeman 2015 as cited in Martins 2017, p. 106). This makes for a sophisticated, complex depiction of a feminist character of whom modern audiences revere.

Amy recites the ‘Cool Girl monologue’ – a now-viral moment from the film as observed on TikTok, namely. It is a key memorable moment because the descriptions of the conscious and unconscious efforts of women to satisfy the male gaze are incredibly relatable; ‘Cool girl never gets angry at her man. She only smiles in a chagrined, loving manner’ (Fincher 2014, 1:10:42). The monologue implies that men worship women who are implicit and comfortable with their faults. TikTok contains 20 million views of videos with the hashtag #amydunneapologist and, more notably, 630 million views of #gonegirl, with almost every video being an edit of Amy. Her popularity as a ‘feminist icon’ reflects the cultural zeitgeist of disillusionment with the glorification of the successful, lazy man who ‘always gets to be the good guy’ – the punishment of such being a ‘cultural backlash’ in Gone Girl (The Take 2020, 11:50). Archer (2017) recites the film as a reflection of this culture in the media, one which is central to both Nick and Amy’s concerns – their respective narration being coined as what is becoming ‘the mind game film’ (p. 4, 7). Amy’s essential characterisation of being a ‘feminist symbol’ is thus a crucial component in the film’s success in engaging the populace, of which Gone Girl should be deemed a ‘classic’.

Gone Girl is swiftly becoming a film which is to be remembered as a celebration of the complex ‘femme fatale’ – a character of whom female audiences identify with under the patriarchy; a culture which continuously attempts to polish them down. The film’s grounding in many genres, including thriller, horror and film noir, reflects its perception in culture – one which is treasured by feminist audiences and challenged as destructive by others. According to the argument that ‘classic texts’ are those which sophisticatedly represent themes which speak to the human spirit of the populace, Gone Girl is a triumph in conveying female rage. The contemporary audience, of whom is permeated by competitive consumer culture and misogyny, feels represented by the theme of marriage, the narrative of gender dynamics and the characterisation of Amy Dunne as perceived by the socio-cultural support of the film. It is highly understated that Gone Girl should therefore be considered a ‘contemporary classic text’.

Works Cited

Archer, N. (2017). Gone Girl (2012/2014) and the Uses of Culture. Literature/Film Quarterly, 45(3), 1-18. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48678553.

Calvino, I. (1986). Why read the classics? In Creagh, P (Ed.), The New York review of books, 33(15), pp. 19–20. https://curtin.alma.exlibrisgroup.com/view/delivery/61CUR_INST/12228298360001951.

Fincher, D. (Director). (2014) Gone Girl [Film]. Regency Enterprises; TSG Entertainment. https://www.disneyplus.com/en-gb/movies/gone-girl/53SdYxRQh07B.

Lee, C. (2023). Modern Horror [iLecture]. Blackboard. https://echo360.net.au/section/c0daf4b1-cc98-4a11-bd24-6ed5c0ac7fff/home.

Martins, A. C. (2017). Seduction and Mutually Assured Destruction: The Modern “Femme Fatale” in “Gone Girl”. In C. Martins & M. Damásio (Eds.), Seduction in Popular Culture, Psychology, and Philosophy (pp. 90-111). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-0525-9.ch005.

Osborne, P. (2017). “I’m the Bitch that Makes You a Man”: Conditional Love as Female Vengeance in Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl. Gender Forum, (63), 4-29,79. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/i-m-bitch-that-makes-you-man-conditional-love-as/docview/1941281986/se-2.

Stratton, B. (2020). Altering the Hypermasculine Through the Feminine: Female Masculinity in Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl. Clues, 38(1), 19-27. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/altering-hypermasculine-through-feminine-female/docview/2429068576/se-2.

The Take. (2020, December 27th). Why You Root for Gone Girl’s Amy Dunne [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/ok7YyNnmpMo.

Leave a comment